School Meals Leads to Healthy Body Supports Healthy Learning Peer Reviewed Articles

- Research article

- Open Admission

- Published:

Free school meals every bit an approach to reduce health inequalities amidst 10–12- year-onetime Norwegian children

BMC Public Wellness volume 19, Article number:951 (2019) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Children spend a considerable amount of time at schoolhouse and consume at to the lowest degree one repast/24-hour interval. This written report aimed to investigate if a free, healthy schoolhouse meal every 24-hour interval for one school yr was associated with children's intake of healthy foods at school, weight status and moderating effects of socio-economical status.

Methods

A non-randomized study design with an intervention and a control group was used to mensurate modify in children'southward dietary habits at lunchtime. In total, 164 children participated; 55 in the intervention group and 109 in the control group (baseline). Intervention-children were served a free, healthy school meal every school day for one year. Participating children completed a food frequency questionnaire at baseline, at v months follow-up and afterward one year. Children's anthropometrics were measured at all iii timepoints. Intervention furnishings on children's Healthy food score, BMI z-scores, and waist circumference were examined by conducting a Repeated Measures Multivariate ANOVA. Moderating effects of children's gender and parental socio-economic status were investigated for each outcome.

Results

A meaning intervention effect on children's outcomes (multivariate) between baseline and subsequently 1 twelvemonth (F = ii.409, p < 0.001), and between follow-up 1 at five months and after i twelvemonth (F = 8.209, p < 0.001) compared to the control group was plant. The Univariate analyses showed a greater increase in the Salubrious food score of the intervention grouping between baseline and follow-upwardly ane (F = iv.184, p = 0.043) and follow-up 2 (F = 10.941, p = 0.001) compared to the command group. The intervention-children had a significant increase in BMI z-scores between baseline and follow-upwards 2 (F = 10.007, p = 0,002) and betwixt follow-up one and 2 (F = 22.245, p < 0.001) compared to a decrease in the command-children. The intervention-children with lower socio-economic status had a significantly higher increase in Good for you nutrient score between baseline and follow-up 2 than the control-children with lower socio-economic status (difference of 2.eight versus 0.94), but non among children with college socio-economic status.

Conclusions

Serving a free schoolhouse meal for 1 year increased children's intake of healthy foods, especially amidst children with lower socio-economical status. This report may contribute to promoting healthy eating and suggests a style frontward to reduce wellness inequalities among schoolhouse children.

Trial registration

ISRCTN61703361. Date of registration: December third, 2018. Retrospectively registered.

Background

A healthy diet is key to wellness. A healthy diet among children and adolescents also protects against not-infectious disease (NCDs) later in life [1]. Healthy dietary habits established early in life tend to persist into adulthood and thereby promote lifelong wellness [2, 3]. Childhood obesity is considered a serious public health claiming and tends to track into adolescence and adulthood [four,5,6]. A salubrious diet is considered a main driver to sustain a good for you weight throughout life [iii].

In a public health perspective, schools are ideal settings to promote salubrious eating habits early in life since children consume at least ane master meal per day at school. Socio-economical status (SES) in families is associated with children's diet, i.e., lower SES families tend to have more unhealthy dietary habits [7, 8]. In Norway, the vast majority of children (96%) attend public schools [9]. Thus, socio-economic inequalities in healthy eating/health may be reduced if all children eat a free, good for you meal at schoolhouse [ten]. In Norway there is in full general no school meal organisation where food is provided (neither free nor parent paid), and the children typically bring packed luncheon from home. Norwegian school children traditionally swallow a cold bread meal during schoolhouse hours [11]. Challenges with the traditional packed dejeuner are that some children bring an unhealthy lunch to school, and children may also skip lunch due to non bringing any lunch [12]. In 2015, renewed and comprehensive guidelines for the Norwegian school repast were introduced, to raise more than awareness in this regard [xiii]. Among the Nordic countries, Denmark has similar school meal arrangement as Norway (i.e. packed dejeuner from home), while Sweden and Finland take served a warm schoolhouse meal every 24-hour interval for several years, gratis of cost for the children [14].

Only ane intervention study in Norway has previously assessed the effect of serving a gratuitous school dejeuner on dietary habits and body mass index (BMI) among 9th graders [15]. The intervention period was relatively short (4 months). Ask et al. found that serving a gratuitous, healthy school luncheon did non pb to an improved intake of fruit, vegetables, low-fat milk and whole-grain staff of life, nor reduced intake of unhealthy snacks, and BMI increased amongst the boys in the intervention group compared to the control group, but not among the girls [15]. No moderating effects of SES was assessed.

School-based interventions intend to decrease social inequalities among children and adolescents, just sometimes the opposite may occur; children of higher educated parents seem to benefit more from interventions than children of lower educated parents [16]. The aim of this study was to appraise the issue of 1 year of serving a complimentary school repast on dietary habits at school and weight status among 10–12-year- erstwhile's in Norway, too as to investigate the moderating effect of SES on the intervention effects.

Methods

This present study is part of the School Meal Projection in Southern Norway [17] which had a non-randomized design with one intervention grouping and i control grouping. The baseline data was collected in August/September 2014, and follow-up data was collected in January 2015 and in June 2015. The school children answered a food frequency questionnaire at school, and height, weight and waist circumference were measured at all time points.

Content of the intervention

A good for you, cold school meal free of accuse was served every school 24-hour interval for 1 yr to the children in sixth grade at one simple school in Southern Norway. The intervention has previously been described past Illokken et al. [17], and was based on the current national dietary guidelines in Norway and consisted of whole-grain breadstuff, good for you spread and fruit and vegetables (FV). Some children drank milk and the others were encouraged to drink water. The nutrient was served on large platters, and the children helped themselves. The children consumed the food together around i or two tables in the classroom, which represented a social arena for the meal. A teacher was e'er nowadays during the meals.

Sample and procedure

A local cook prepared and served the healthy school repast every day. In social club to make the intervention feasible, a convenience sample was chosen and all children in one school class were allocated either to the intervention or the control group. Two schools were included in the project, and all participating children had an age-range from x to 12 years (5th – 7th course) [17]. In ane school at that place was both an intervention group and a control group, and in the other school 3 was only a control grouping. Both schools were located in a rural expanse in the same county, and they were similar in schoolhouse size. Active parental consents were required by the Norwegian Centre for Inquiry Information and before baseline measurements, written consents to participate in the School Repast project were nerveless. The participating children were made aware of the possibility to withdraw from the project. Project workers were present when the children filled out the questionnaires (by pen and paper) during a school lesson, in guild to clarify possible misapprehensions. The children were asked to consider their eating habits for the previous 2 weeks when filling out the questionnaires.

Measures

Diet was assessed by a food frequency questionnaire. The questions had half dozen different response alternatives, ranging from "never" to "every day", and included questions on food habits at schoolhouse with the usual packed luncheon (baseline and follow-ups in the control group) and the served schoolhouse meal (follow-ups in the intervention group). Diet was assessed with items derived from previous validated questionnaires [17].

A Healthy nutrient score (HFS) based on xiii selected nutrient items was adult [17]. The food frequency questionnaire included more than the selected 13 items; notwithstanding, they were chosen in order to differentiate betwixt the children in the sample who had a healthier intake at lunchtime compared to those who had an unhealthier intake. Hence, both healthy and unhealthy food items were included in the score. Healthy nutrient items, e.thou. whole-grain breadstuff, fish, berries and FV and unhealthy food items, due east.g. white breadstuff, noodles, chocolate spread, crackers and pancakes were included to investigate possible change in the consumption of these. Response alternatives of healthy and unhealthy food items were recoded into salubrious (=ane) or unhealthy (=zero) depending on frequency of intake (Table 1). Missing values were included as zero. The total food score included a summed value from all the xiii recoded scores. The HFS ranged from ane to 13, i.e. a college HFS resembled a higher intake of healthy nutrient items.

Parents' level of education was assessed in the parent questionnaire by 2 items: "What is your highest level of completed instruction?" with iv response options; "master school (elementary school or lower secondary schoolhouse)", "upper secondary school", "3-4 years of college or academy" and "5 or more years of college or university" and "what is your spouse/partner'due south highest level of completed instruction?". The response options were the aforementioned as the previous item, merely also included; "I practise not take a spouse/partner". The parents' educational level was a proxy for SES. Both scores were combined and dichotomized into "low SES" (both parents having completed master school and upper secondary school) and "high SES" (at least one parent having completed 3–4 years and more than than five years of college/university) [18].

Body top, weight, and waist-circumference (WC) of the children were measured at schoolhouse. The methodology has previously been published [17]. BMI z-scores were calculated according to the International Obesity Task Force criteria (IOTF) [19].

Statistical analysis

Preliminary analyses consisted of descriptive statistics of sample characteristics and normality of the event variables was checked. Participants' characteristics at baseline were compared by independent sample t-tests for continuous variables and by chi-square tests for chiselled variables to notice baseline differences betwixt the control and the intervention group. No drop-out analysis was conducted given that few children were lost to follow-up.

Considering baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between intervention and control group apart from gender, which is included as a moderator, they were not used equally covariates in further analyses. Intervention effects on children'due south Healthy food score, BMI z-scores, and waist circumference were examined past conducting a Repeated Measures Multivariate ANOVA with time as within cistron (differences between baseline and follow-upwardly 1 and follow-upward 2, and betwixt follow-up i and follow-upwardly 2) and condition (intervention group, control grouping) as betwixt factor. To examine potential moderating effects of children's gender (boys versus girls) and parental SES (lower versus college SES), a three-way interaction consequence (time*condition*moderator) was investigated for each outcome. The Repeated Measures Multivariate ANOVA was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0. All analyses used complete cases for the outcome variables (excluding the children that had missing outcome data for 1 of the follow-ups), and p-values of < 0.05 were considered meaning.

Results

Sample characteristics

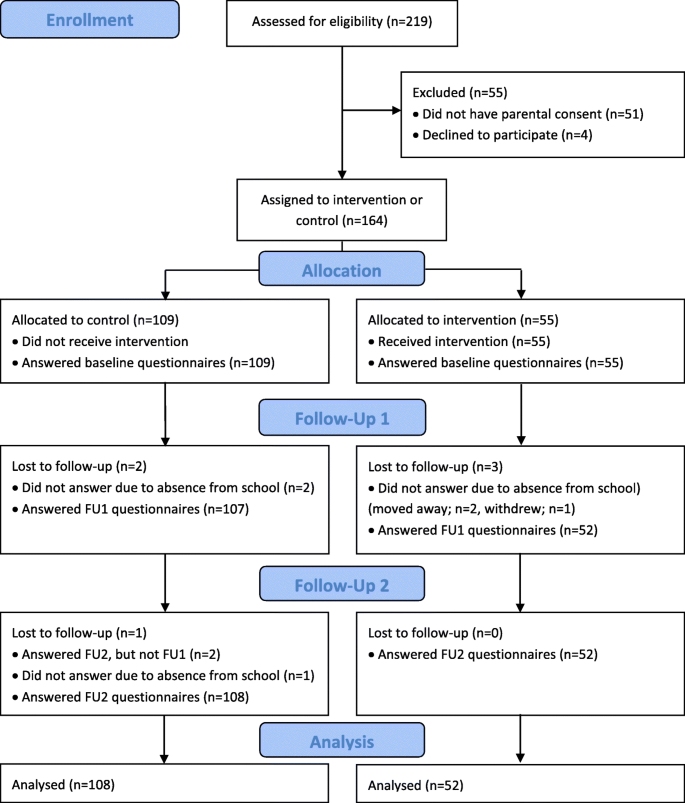

A total of 219 children were invited to join the project and 168 of the invited children received active parental consent, still four children chose not to participate. The written report sample thus consisted of 164 children at baseline (participation rate 75%). The intervention group consisted of 55 children from 6th course (participation rate 96%), while the control group consisted of 109 children from 5th, 6th and 7th course (participation charge per unit 67%) at baseline (T0). A total of 154 parents participated at baseline (participation rate 70%). In the get-go follow-up (T1), 159 children participated (participation rate 73%). In the second follow-upwardly (T2), 160 children participated (participation rate 73%). The reason why a few children were lost to follow-up in T1 and T2 are described in Fig. ane.

Flow Diagram Children

Baseline characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 2. Both groups are comparable at the baseline, apart from significant gender differences. The intervention group included more boys and the control group more girls.

Intervention effects on children's good for you food score and anthropometrics

The Repeated Measures Multivariate ANOVA assay showed a significant outcome of the intervention on children'due south outcomes between baseline and follow-up two (F = 2.409, p < 0.001), and between follow-up one and 2 (F = 8.209, p < 0.001). The Univariate analyses indicated a greater increase in the Healthy food score of the intervention group between baseline and follow-up one (F = iv.184, p = 0.043) and follow-up 2 (F = 10.941, p = 0.001) compared to the control group. No pregnant differences were found for the Salubrious food scores between Follow-upward 1 and 2 of both groups. Unexpectedly, the two-style interaction effects showed that the intervention-children had a significant increase in BMI z-scores between baseline and follow-upward two (F = x.007, p = 0,002) and between follow-upwardly one and 2 (F = 22.245, p < 0.001) compared to a decrease in the control-children. No significant differences were constitute for the changes in BMI z-scores from baseline to follow-upwardly 1. In improver, no significant intervention furnishings were found on waist circumference between baseline and both follow-ups. The results of these analyses tin be found in Table three.

Moderating effects of children's gender and parental SES

From baseline to follow-upward 2, the fourth dimension*group*SES interaction effect was pregnant for the Salubrious food score. Stratified analyses showed a significant time*group two-way interaction for the Healthy food scores in the lower SES group (F = vii.762, p = 0.007) compared to a non-meaning two-mode interaction outcome in the higher SES group. The intervention-children with a lower SES had a significantly higher increase in Salubrious nutrient score betwixt baseline and follow-up 2 than the control-children with a lower SES (i.east., a departure of 2.8 compared to 0.94). No significant difference in Good for you nutrient score was plant between the intervention and control children with a higher SES. The results of these moderation analyses tin be found in Table three, the stratified analyses are not shown.

Give-and-take

In this study we found that serving a gratuitous school repast for i year increased children's intake of healthy foods, particularly among children with lower socio-economic status. Nosotros found a greater increase in the Good for you nutrient score of the group receiving gratuitous school lunch betwixt baseline and follow-upwardly 1 and between baseline and follow-up ii compared to the control group. This indicates that the children in the intervention group inverse their diet in a more favourable style during the intervention period compared to the control group. This contradicts the findings of Ask and colleagues [15] which establish that a gratuitous, healthy school lunch (wholemeal breadstuff, different kinds of unsweetened spread, depression-fat milk and fruit/vegetables) to ninth graders for four months did not improve the food score, i.e. intakes of fruit, vegetables, depression-fatty milk and wholegrain breadstuff, or reduce the intake of snacks, sugar-sweetened beverages and candy/chocolate [15]. Our findings are in line with 2 other studies examining school meal and eating habits among schoolhouse children in Republic of finland, which establish that intake of gratis school meals was associated with healthier eating habits, both at school and outside school [twenty, 21].

No significant differences were constitute for the Salubrious nutrient scores between follow-up one and two of both groups. This may exist due to that fact that the positive changes had already happened in the intervention group from baseline to follow-up ane, and that no differences were expected for the control grouping. Nudging child diet in the right direction is optimal for child development and health. According to Heckman and colleagues [22, 23] pocket-size positive changes early in life are valuable for the individual'due south future wellness and for the society in a public health perspective. A specific cost-benefit for a school meal has non been calculated. However, calculations regarding increasing kid intake of one fruit or vegetable per twenty-four hours done by Norwegian health government, prove that there are large health and economic benefits [24]. Our results are the first to show dietary improvements later a costless school meal in Norway among both boys and girls. A previous intervention in Norway where free breakfast was served to 10th graders for four months, reported an improved food pattern amid boys only in the intervention grouping compared to the control group [25]. Even so, since this was a breakfast intervention compared to lunch, the results are not completely comparable.

The intervention-children with a lower SES had a higher increase in Healthy food score between baseline and follow-upward 2 than the control-children with a lower SES. No meaning difference in Healthy food score was plant between the intervention and control children with a higher SES. This finding may point that by introducing a healthy schoolhouse lunch, social inequalities can exist reduced. In that location are large socioeconomic differences in diet and health, adding to the burden of lower SES families [26,27,28]. As interventions have been reported to increase social inequalities in wellness [16] with children of college educated parents benefitting most from interventions, this written report showed the opposite by only having upshot in lower socio-economic groups. As the master public wellness policy goal is to reduce social inequality in health in Norway, this study shows that a free healthy schoolhouse meal may reduce such differences. Such a program will demand alter of policy and increased funding to be conducted. As milk and fruits (in some schools) are available to buy at Norwegian schools, one could get-go by including healthy meals as a part of these structures. However, in general, nosotros know that interventions to promote salubrious eating is more effective in lower SES groups if information technology is gratis or at reduced price [29]. Our results are in line with those seen for complimentary fruit and vegetables at schoolhouse, namely an increase in intake and reduction in social inequality [thirty, 31]. All the same, the overall quality of diet was improved in our study, not merely FV, which would be fifty-fifty more benign. Findings from a systematic review in Europe signal that children from lower SES may profit from schoolhouse-based interventions promoting a healthy diet [32].

Unexpectedly, the two-way interaction effects showed that the intervention-children had a pregnant increase in BMI z-scores between baseline and follow-up 2 and betwixt follow-upward 1 and ii compared to a subtract in the command-children. No significant differences were found for the changes in BMI z-scores from baseline to follow-upward one. Ask and colleagues [15] found that BMI for girls in the intervention group (free school lunch for iv months) did not increase, while a meaning increase was seen among the boys in both intervention and control group. Both the Ask written report and the present report accept few participants, and this upshot may be due to chance. The electric current project had no intention of children reducing their weight and at the age of ten–12, children are in growth, and then ordinarily we would not expect significant changes in BMI afterwards one twelvemonth. The purpose was to contribute to healthy eating at school and long-term healthy weight status. In this regard, one year is not long-term. Also, the children were served luncheon from a buffet and this may have contributed to larger portions in the beginning. It is hard to say whether these differences indicate a good for you or unhealthy weight trajectory for the intervention group. The same associations were non seen regarding waist circumference where no change was found. The effect of a gratuitous meal on weight should be investigated further.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The duration of the intervention (serving a free healthy schoolhouse meal) was one total school year, which may be considered as a long-lasting intervention. The design with an intervention grouping and a control group, and the high participation rate are other strengths. Trained projection workers collected all data in the study to ensure consistency and the items in the questionnaires were validated.

There are also some limitations to our study. The non-randomized report blueprint and the fact that the intervention group was located at the aforementioned schoolhouse as part of the command groups represents a substantial limitation. However, the children in the intervention grouping were in a totally different office of the school building than the control grouping, minimizing the chance of confounding, e.g. when the school repast was brought to schoolhouse every day. Differences in historic period as well as differences in group size betwixt the intervention grouping and the control group constitute another limitation. The present study is based on self-reported data relying on retentiveness which could introduce response bias [33]. Too, all the children were aware of the purpose of the study, and this might have influenced their answers. The representativeness and generalizability of this study might take been influenced by these limitations, and the results should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Determination

This report finds that at complimentary healthy school meal for one yr improves overall nutrition at school especially among those needing it the most; children from lower socio-economic status. The written report likewise reports an increase in BMI z-score for the intervention grouping, however no alter in waist circumference. These results should be studied further. Regardless of relation to weight, nudging the nutrition in the right management has large potential health benefits for the children and economic benefits for the society. Costless school meals may have a great potential for health promotion and on improving future public wellness measures amongst children.

Availability of information and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the respective author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Trunk mass index

- CG:

-

Control group

- IG:

-

Intervention group

- SES:

-

Socio-economic status

- T0:

-

Baseline

- T1:

-

follow up1

- T2:

-

follow up2

References

-

DevelopmentInitiatives. Global nutrition study: shining a lite to spur activity on diet. Bristol: Evolution Initiatives; 2018. p. 2018.

-

Gorski MT, Roberto CA. Public health policies to encourage healthy eating habits: recent perspectives. J healthc leadersh. 2015;7:81–xc.

-

WHO. Food and nutrition policy for schools: a tool for the development of schoolhouse nutrition programmes in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2006.

-

Lobstein T, Jackson-Leach R, Moodie ML, Hall KD, Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA, et al. Kid and adolescent obesity: part of a bigger flick. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2510–xx.

-

WHO. Report of the commission on ending childhood obesity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

-

Singh Every bit, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9(v):474–88.

-

Richter A, Heidemann C, Schulze MB, Roosen J, Thiele S, Mensink GB. Dietary patterns of adolescents in Frg--associations with nutrient intake and other health related lifestyle characteristics. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:35.

-

Drouillet-Pinard P, Dubuisson C, Bordes I, Margaritis I, Lioret S, Volatier JL. Socio-economic disparities in the diet of French children and adolescents: a multidimensional outcome. Public Health Nutr. 2017;xx(5):870–82.

-

Statistics Kingdom of norway. Pupils in primary and lower secondary schoolhouse [internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.ssb.no/en/utdanning/statistikker/utgrs.

-

Nilsen SM, Krokstad Southward, Holmen TL, Westin S. Adolescents' health-related dietary patterns past parental socio-economical position, the Nord-Trondelag health study (Chase). Eur J Pub Health. 2010;20(three):299–305.

-

Hansen LB, Myhre JB, Johansen AMW, Paulsen MM, Andersen LF. UNGKOST 3 Landsomfattende kostholdsundersøkelse blant elever i iv. og eight. klasse i Norge. Oslo; 2015.

-

Kainulainen K, Benn J, Fjellström C, Palojoki P. Nordic adolescents' school luncheon patterns and their suggestions for making healthy choices at school easier. Appetite. 2012;59(one):53–62.

-

Helsedirektoratet. Kostråd fra Helsedirektoratet [Dietary advice from the Norwegian Directorate of Health] 2015 [Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/search/_/attachment/inline/80f68126-68af-4cec-b2aad04069d02471:dcb8efdbe6b6129470ec4969f6639be21a8afd82/Helsedirektoratets%20kostr%C3%A5d%20-%20engelsk.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2019.

-

Ray C, Roos E, Brug J, Behrendt I, Ehrenblad B, Yngve A, et al. Role of free school lunch in the associations between family-environmental factors and children's fruit and vegetable intake in 4 European countries. Public Health Nutr. 2013;sixteen(6):1109–17.

-

Ask AS, Hernes S, Aarek I, Vik F, Brodahl C, Haugen Thousand. Serving of free school lunch to secondary-school pupils - a airplane pilot study with health implications. Public Wellness Nutr. 2010;13(2):238–44.

-

Grydeland M, Bjelland Yard, Anderssen SA, Klepp KI, Bergh IH, Andersen LF, et al. Furnishings of a 20-calendar month cluster randomised controlled school-based intervention trial on BMI of school-aged boys and girls: the HEIA report. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(9):768-73.

-

IlloKken KE, Bere E, Overby NC, Hoiland R, Petersson KO, Vik FN. Intervention study on school meal habits in Norwegian 10-12-year-onetime children. Scand J Public Wellness. 2017;45(5):485–91.

-

Brug J, van Stralen MM, Te Velde SJ, Chinapaw MJ, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lien N, et al. Differences in weight condition and energy-residuum related behaviors among schoolchildren beyond Europe: the Free energy-project. PLoS One. 2012;seven(4):e34742.

-

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1240–iii.

-

Raulio South, Roos E, Prattala R. School and workplace meals promote healthy food habits. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(6A):987–92.

-

Tilles-Tirkkonen T, Pentikainen S, Lappi J, Karhunen 50, Poutanen K, Mykkanen H. The quality of school lunch consumed reflects overall eating patterns in 11-16-year-old schoolchildren in Republic of finland. Public Wellness Nutr. 2011;14(12):2092–8.

-

Halfon Northward, Hochstein M. Life course health development: an integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. Milbank Q. 2002;80(3):433–79 iii.

-

Conti G, Heckman JJ. The developmental approach to child and developed health. Pediatrics. 2013;131(Suppl 2):S133–41.

-

Sælensminde G, Johansson L, Helleve A. Fruit and Vegetalbe intake in school - Socio-economical evaluation Oslo; 2015 31.03.2016.

-

Enquire AS, Hernes S, Aarek I, Johannessen 1000, Haugen M. Changes in dietary pattern in 15 year old adolescents following a 4 month dietary intervention with schoolhouse breakfast - A pilot report. Nutr J. 2006;5(1):33.

-

Appelhans BM, Milliron BJ, Woolf M, Johnson TJ, Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, et al. Socioeconomic status, energy cost, and nutrient content of supermarket food purchases. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(iv):398–402.

-

Darmon North, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict nutrition quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(five):1107–17.

-

Giskes K, Avendano One thousand, Brug J, Kunst AE. A systematic review of studies on socioeconomic inequalities in dietary intakes associated with weight gain and overweight/obesity conducted among European adults. Obes Rev. 2010;xi(6):413–29.

-

McGill R, Anwar E, Orton L, Bromley H, Lloyd-Williams F, O'Flaherty M, et al. Are interventions to promote good for you eating equally effective for all? Systematic review of socioeconomic inequalities in impact. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:457.

-

Bere E, Hilsen 1000, Klepp Thou-I. Effect of the nationwide complimentary school fruit scheme in Norway. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(4):589–94.

-

Overby NC, Klepp KI, Bere E. Introduction of a school fruit program is associated with reduced frequency of consumption of unhealthy snacks. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(5):1100–3.

-

Van Cauwenberghe East, Maes Fifty, Spittaels H, van Lenthe FJ, Brug J, Oppert JM, et al. Effectiveness of schoolhouse-based interventions in Europe to promote healthy diet in children and adolescents: systematic review of published and 'grey' literature. Br J Nutr. 2010;103(6):781–97.

-

Willett West. Food frequency methods nutritional epidemiology 3ed. New York: Oxford university press; 2013.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all participating children and parents involved in the School Repast Project, the teachers and authoritative staff at the two simple schools, and the local cook for the grooming and serving the school repast.

Funding

The University of Agder supported the piece of work in The Schoolhouse Meal Project. Kiwi Birkeland, Bakers Lillesand, Birkeland Medical Centre, The Norwegian Women's Public Wellness Association and Aust-Agder canton quango supported the projection but had no role in the design of the study and information collection, analyses, and interpretation of data or in writing of the manuscript.

Author data

Affiliations

Contributions

FNV and NCØ designed the written report. FNV was the projection leader and involved in field work and data drove. FNV drafted the manuscript. WvL performed the analyses and wrote the results. NCØ was involved in interpreting the data and writing the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding writer

Ideals declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Schoolhouse Meal Project obtained ethical clearance from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, and the Upstanding commission of Faculty of Health and Sport Sciences at the Academy of Agder. Consent was obtained from a parent or guardian on behalf of any participant under the age of xvi. Parents and children were given written information about the projection and consented to participate by filling in a written consent class.

Consent for publication

Non applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher'southward Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided yous give advisable credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and point if changes were made. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/cypher/1.0/) applies to the information made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vik, F.N., Van Lippevelde, W. & Øverby, N.C. Free school meals every bit an approach to reduce health inequalities among 10–12- yr-old Norwegian children. BMC Public Health 19, 951 (2019). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12889-019-7286-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12889-019-7286-z

Keywords

- Children

- Free school meal

- Intervention

- Weight status

- Salubrious nutrient score

- Socio-economic condition

- Kingdom of norway

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-019-7286-z

0 Response to "School Meals Leads to Healthy Body Supports Healthy Learning Peer Reviewed Articles"

Post a Comment